Interior design

A unique piece of history

To enter the Carrer de Muntaner house is to be swept back in time and to plunge into the opulence and sophistication of a bygone era when, if you were wealthy, it was important to show it. From the magnificent marble staircase to the tiniest ornamental details, these spaces are exceptional examples of the taste of a whole social class, which, in line with the regime at the time, sought to emphasise its power.

Though Muñoz Ramonet maintained the architectural structure designed by Sagnier, he had all the interior spaces fully renovated by Herráiz y Cía., one of the most prestigious decoration companies in Spain, and especially Madrid, at that time. Antonio Herráiz was the Spanish aristocracy’s favourite interior decorator who designed furniture used in government ministries, hotels and homes. Specialising in luxury furniture and bronze pieces, he was at his busiest in the 1940s and 1950s.

An interior with grand salons, à la Proust

The inside of the house is arranged around a large hall crowned by a skylight, with a series of iconic rooms leading off it. These include the large dining room decorated with paintings inspired by Homer’s The Odyssey, and the ‘Goyaesque’ room, in Charles IV style, adorned with mural paintings depicting the people of Madrid in traditional dress. A consistent interior design prevails throughout the entire interior. Based on the European styles of Baroque and Rococo salons and furniture, a series of rooms is sumptuously decorated with mirrors, boiserie, plaster reliefs and cornices, gilding, marble floors and decorative parquet flooring. These include the music or mirror room, with its imposing grand piano by the prestigious French company Érard from the late nineteenth century; the ballroom, decorated in the style of the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century kings of France; and the apéritif room, which evokes the decoration of British gentlemen’s clubs. It is not hard to imagine the parties and receptions held here in the 1950s with the leading figures from Catalan civil society.

The ground-floor hall houses a sumptuous staircase that leads to the first floor. This floor includes the family’s private rooms – identified as belonging to the man of the house, the lady of the house and the daughters, along with the day-to-day rooms – all arranged carefully around a Neo-Renaissance gallery that overlooks the main vestibule, with elegant columns and semicircular arches.

Following the 1950 renovations, the second floor – once reserved for servants – became a space dedicated to leisure, with a library/billiards room, a cinema room and guest bedrooms. Meanwhile, the laundry rooms in the basement were turned into rooms for the domestic staff, a kitchen, a cold room and a cellar, in line with the British tradition of putting the wealthy classes at the top of a building and the working classes below.

A consistent interior in a classical style

Antonio Herráiz, who had decorated embassies and rooms in the homes of Princess María Teresa and Prince Carlos and in the Royal Palace of Madrid, designed a consistent interior in a classical style, within which the ground-floor rooms were especially noteworthy. In these rooms, decorative art objects such as rugs, tapestries, bronzes, ceramics and furniture combine with ornamental elements applied to the architecture, including murals, cornices, doors and more, to create a classic, traditional, elegant space.

The house’s furniture is the key to the reproduction of the historicist salons imagined by Herráiz. The furniture evokes the Spanish and European styles of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and possesses great heritage value explained by a context of clear artistic importance.

Each space offers a balanced mix of different models, and Herráiz brings together different fabrics in curtains and tapestries, a colourful palette and variations on similar styles. In the largest rooms, he organises the furniture into small groups, creating a dynamic, varied feel. Some examples of the excellent carpentry work in the house are two bureaus in the ballroom, imitating those kept by Louis XIV in his office in Versailles, and the Ferdinand-style mahogany sofa in the ‘Goyaesque’ room, with cream-coloured sculpted swans on the backrest. The swan motif in this room is repeated in the border of the rug, exemplifying the aforementioned idea of consistent design.

The furniture’s exceptional quality is perfectly complemented by the outstanding metalwork, especially the stunning bronzes. Among the house’s most noteworthy features are imposing chandeliers with hanging strings of cut glass, sets of candelabras that combine cast bronze sculptural elements with coloured marble shafts, and bronze and glass interior doors with transoms decorated with censers and oak and olive leaves.

Following the decorative trends favoured by the postwar bourgeoisie, which emulated the pre-French Revolution aristocratic spirit, each room is adorned with clocks and large ceramic vases from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, imitating French and Saxon porcelain from the eighteenth century. Herráiz’s company itself may very well have provided these imported decorative objects.

Large, handmade wool rugs, with a classical aesthetic, put the finishing touch on the various rooms. Custom-made by Casa Aymat, they carry a host of references to Julio Muñoz Ramonet’s status and social ascent, consolidated through his links with Carmen Villalonga. Each room contains motifs like the cornucopia, the eagle and the swan, while explicit references to family names in the crests and the initials ‘M’ and V’ are incorporated into the designs.

Masters of the applied arts

Little remains of the decoration of the property from the Fabras’ time apart from several vestiges such as the stained glass windows, which boast extraordinary artistic and heritage value. The oldest are found in the chapel in the gallery on the first floor, and were made by Antoni Rigalt & Cia. (1890–1903) between 1901 and 1903 and dedicated to Saint Emily and Saint George. They may have been moved here from the chapel in the first Marquis of Alella’s residence on Rambla de Canaletes. Rigalt’s company was known for being one of the best stained glass workshops in Catalonia. Making this pair of stained glass windows – in a pre–Modernista, historicist style – required a great deal of technical skill. Their polychrome parts display exquisite pictorial treatment and may have been made by Antoni Rigalt himself.

In addition, the skylight in the main lobby was made by Rigalt, Granell & Cia. (1903–1923) – Enric Sagnier’s go-to company – and comes from the workshop’s peak period of production. Installed around 1922, when the finishing touches were being added to the building, the skylight’s design is inspired by the classical style and follows Noucentista tendencies. Muñoz Ramonet then personalised the original stained glass skylight by changing the Marquis’s aristocratic emblems to an ‘M’, the first letter of his surname. The original sketches for the project can be found in the Rigalt collection archive in the Museu del Disseny in Barcelona.

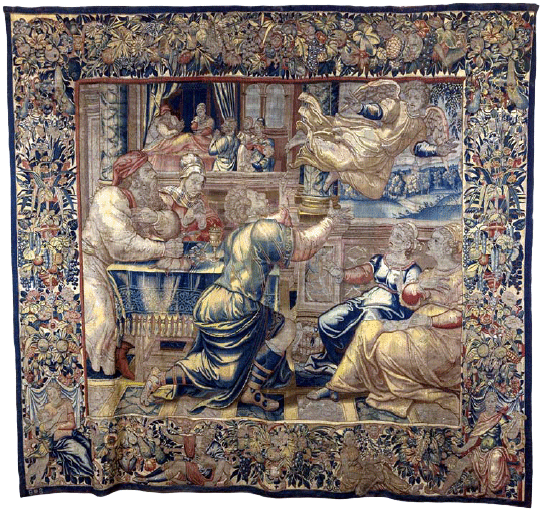

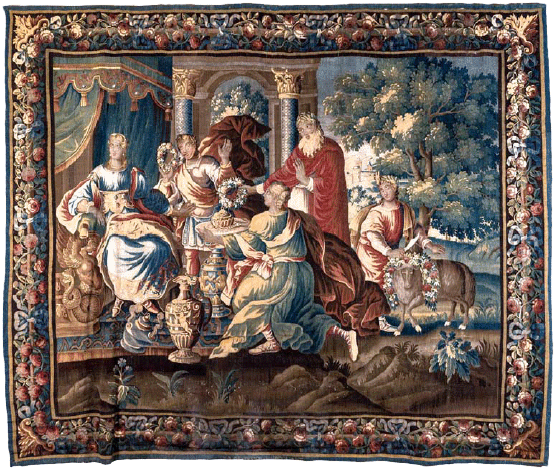

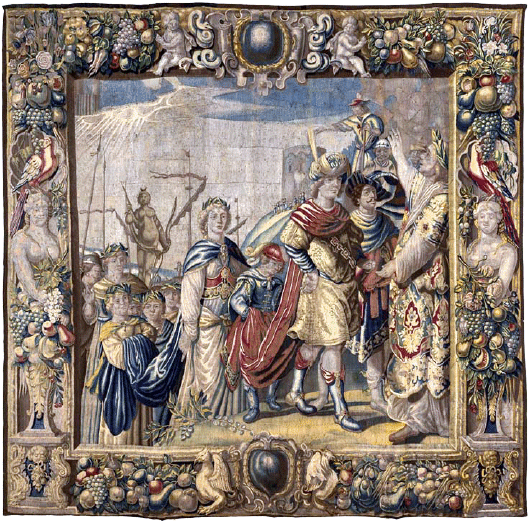

Elsewhere, the home’s tapestries are significant works of art themselves. This set of seven tapestries are from Flanders, France and Holland and date from the sixteenth to the early eighteenth century. The textile art of tapestry, fashionable for centuries, decorated rooms in a solemn, sombre style while making them warmer.

The first set is made up of four tapestries from Brussels, historically, one of the hubs of tapestry production in Europe known for excellent quality. Of these pieces, there are two – one from the sixteenth and one from the seventeenth century – that represent episodes from the lives of Tobias and Joseph, respectively. The other two tapestries, both from the seventeenth century, depict scenes of Venus from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Though they do not carry the highly prized marks of Brussels, they have also been attributed to the Belgian capital.

The second set is made up of two tapestries from Aubusson, France. One of them depicts the marriage of Paris and Helen, both figures from Greek mythology, and dates from the seventeenth century, while the other, from the early eighteenth century, represents an episode from the legend of Cupid and Psyche in the Lucius Apuleius Madaurensis book Metamorphoses. At that time, the Aubusson workshop was skilled enough to compete with the Gobelins Royal Manufactory in Paris.

The third set includes just one tapestry, possibly Dutch, from the seventeenth century, depicting the return of Orestes and Iphigenia to Aulis.