Architecture

A new paradigm for the city

The property is testament to the opulence of the Catalan bourgeoisie around the turn of the century, when Sant Gervasi became an area filled with single-family houses with gardens. It is also one of a few of those early twentieth-century homes that still remains almost entirely intact.

When the nineteenth century was drawing to a close and the Industrial Revolution had created a strong, wealthy bourgeoisie, Barcelona’s high society were starting to move in to their own properties in the city. The opening of the Sarrià train in 1863 enabled many well-off families to move residence to the uptown area.

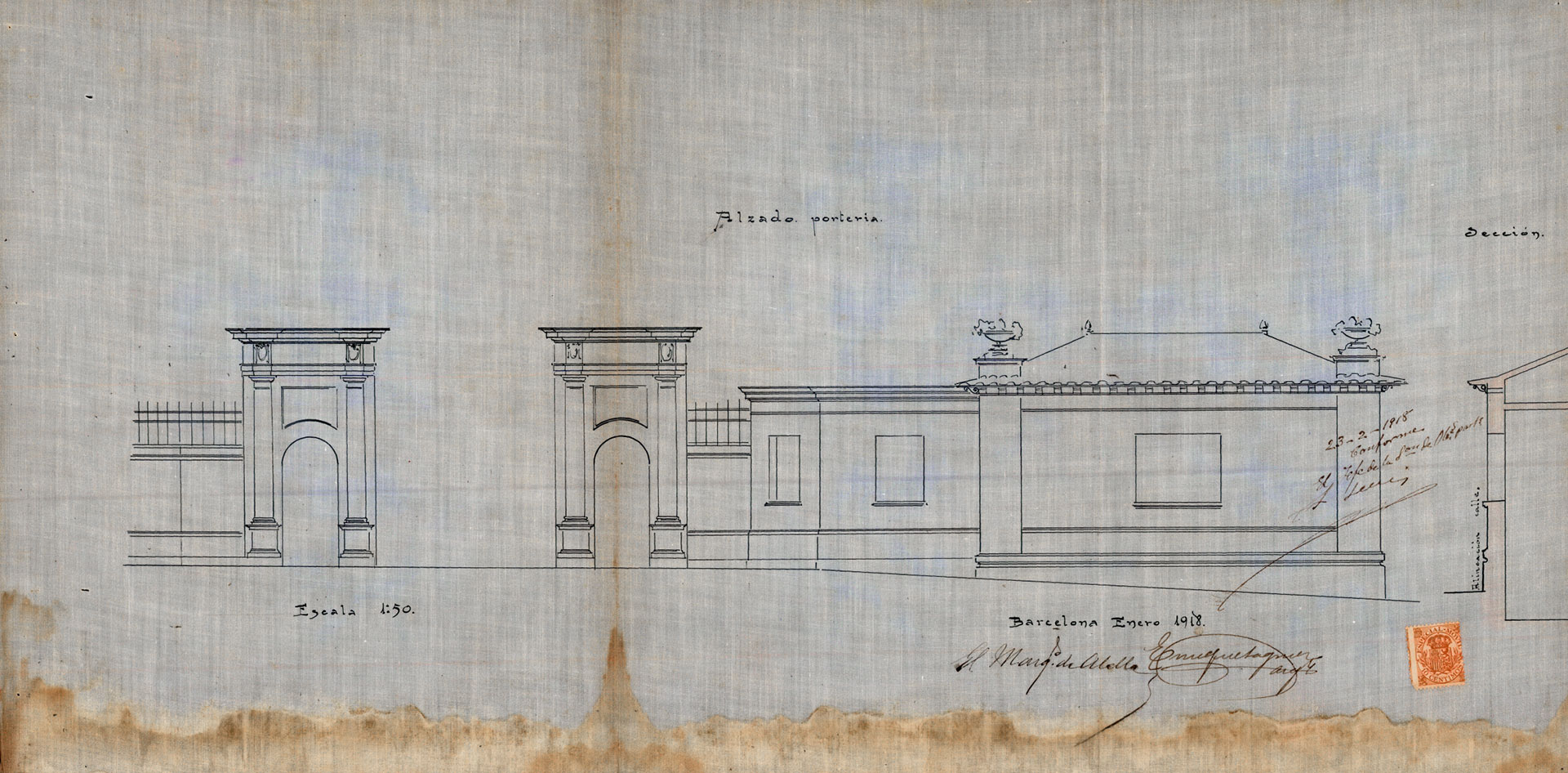

Textile magnate Ferran Fabra i Puig (1866–1944), the second Marquis of Alella and mayor of Barcelona (1922), bought a large plot of land on Carrer de Muntaner – between Carrer de Marià Cubí and Carrer de l’Avenir – and commissioned the architect Enric Sagnier i Villavecchia (1858–1931) to build on it between 1917 and 1922. The project consisted of various houses: the main house on Carrer de Muntaner for Fabra i Puig himself, another on Carrer de l’Avenir for his daughter, and two more on Carrer de Marià Cubí for his sons, which were later sold by their descendants. Sagnier added the porter’s lodge to the property in 1921.

In 1945, the marquis’s granddaughters sold the plot as we know it today – with its fence and the buildings still standing now – to the brothers Julio and Álvaro Muñoz Ramonet. Years later, Julio bought his brother’s share, thus becoming the sole owner of the property in 1952.

Sagnier and the Noucentista tradition

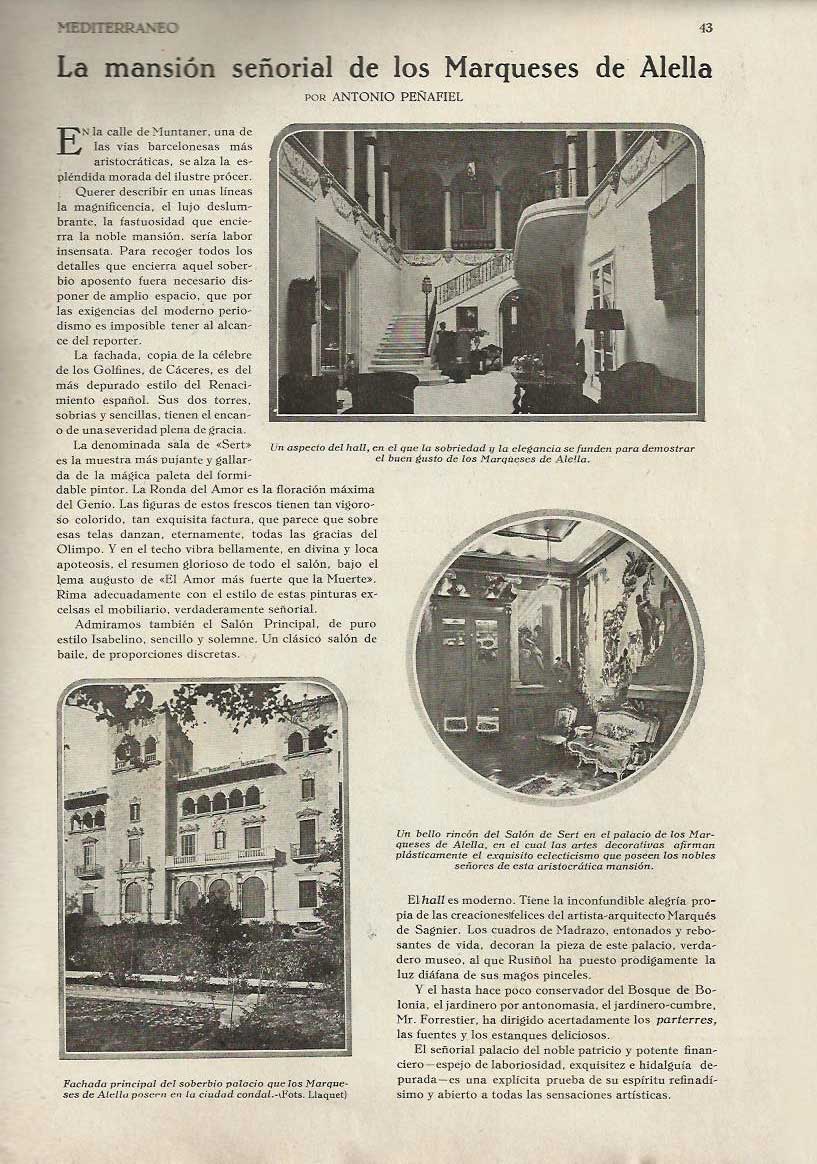

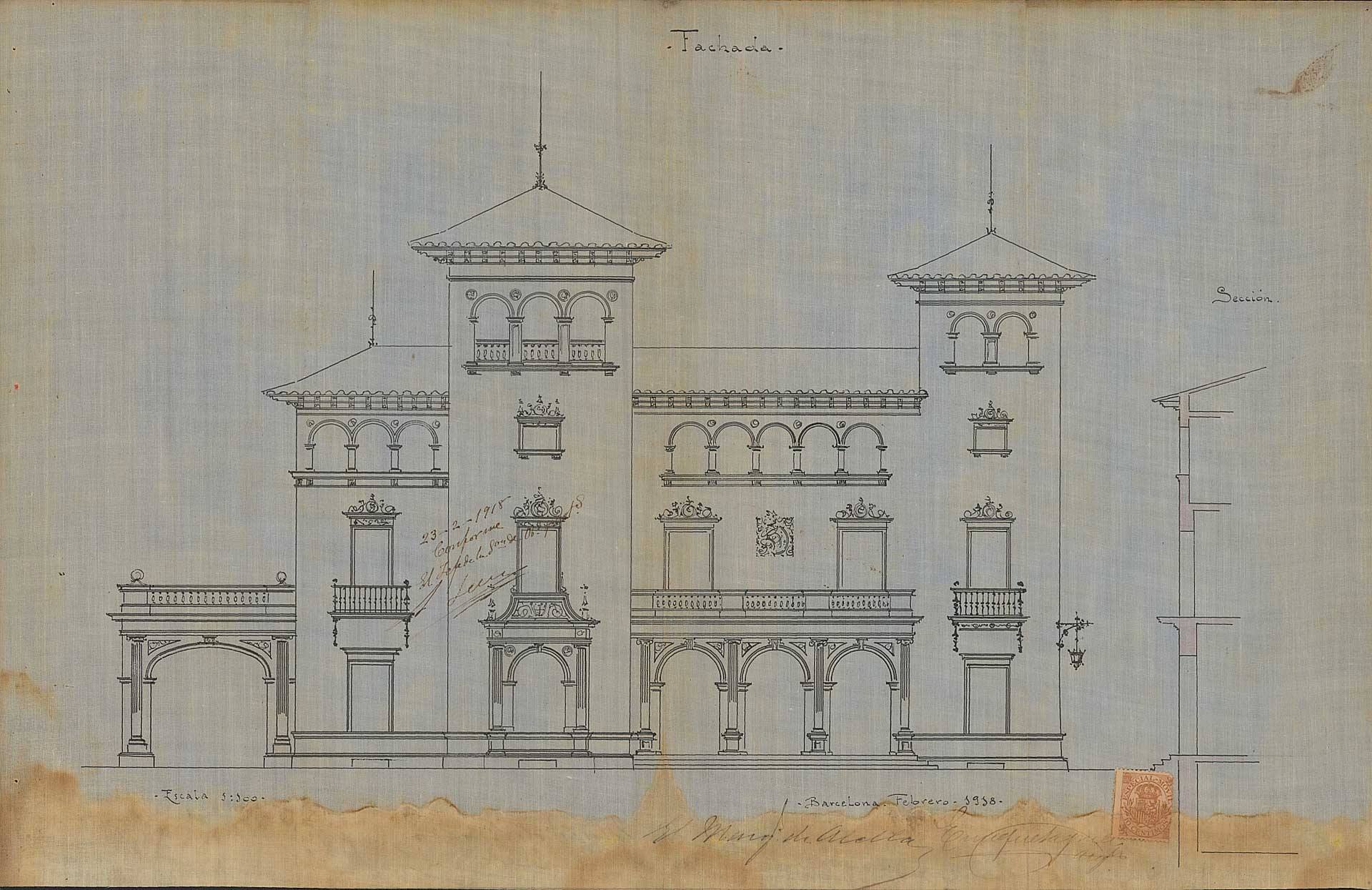

The Renaissance-inspired main house has an area of 2,100 square metres divided into four storeys and a roof terrace with two towers. In the middle of the main façade, the most decorated one, is a triple arcade that looks onto the garden under a balcony with stone bannisters and an upper floor with a gallery that used to be open and features semicircular arches. Here, Sagnier played with openings framed by volutes and sculpted stone corbels, as well as with finials on the towers on the roof terrace, and with balustrades and cornices that evoke the Plateresque tradition of Castilian architecture. The finish on the façades maintains a neat, classicist style characteristic both of Noucentisme and the architect in the buildings he designed during that period. Finally, the perimeter of the building is surrounded by a sunken courtyard topped by wrought-iron railings, which brings natural light into the basement.

Once he had bought the property, Muñoz Ramonet made several changes to the main house, such as adding a floor above the entrance porch and covering the exterior gallery on the second floor. But besides that, practically all of the original structure from Sagnier’s project has been preserved. The Marquis of Alella’s coat of arms is visible on the middle balcony on the first floor, surrounded by volutes and acanthus leaves. There are also outdoor lights, wrought-iron railings and wooden doors, all from the first quarter of the twentieth century.

Surrounded by the garden that creates symmetries with the buildings, visitors can get lost in the simple majesty of all the architectural details and dive into another time.

The house on Carrer de l’Avenir

Also known as the Torre Inés Fabra, the house with an entrance on Carrer de l’Avenir was built for the marquis’s daughter. It has an area of over 820 square metres and four storeys. Enric Sagnier designed a classical-style, Neo-Renaissance building influenced by the French tradition of urban, bourgeois architecture and of hôtels particuliers.

Built with a hip roof, its façades are symmetrical and the rooms are arranged harmoniously around a central, open space and a grand staircase. The interior is made up of large, regular spaces organised in a simple, orderly fashion that always meet at the centre, the hall for each floor, with a straightforward, rational structure.

This internal order is expressed on the outside through the building’s openings, which are placed along vertical axes. The sense of verticality is emphasised by the pilasters embedded on the walls, made from textured stucco imitating stone ashlar, which appear to support the cornice crowning the building. It is worth noting the quality finish on the framing, consisting of moulded stucco displaying a repertoire of classical elements including pilasters, capitals, acanthus leaf corbels, friezes and Corinthian-inspired modillions. The main entrance façade incorporates a set of three stained-glass windows of great artistic importance, attributed to the company Rigalt, Granell & Cia.

As he did with the main house, when Muñoz Ramonet acquired the property, he maintained the architectural structure of the interior layout but tasked Antonio Herráiz with the redecoration project. Still remaining from this renovation project are the grey marble slab and parquet flooring, as well as wooden cladding and doors, plaster mouldings (on the walls, ceilings and the main staircase) and a large cut-glass chandelier that dominates the first two floors. Another noteworthy detail is the delicate decoration in the salonet or lounge on the first floor, with rocaille and high-relief sculpted birds.

Julio Muñoz kept the house for his mother, Florinda Ramonet Sindreu, to live in. When she died, the private rooms and bedrooms were turned into offices and meeting rooms for the family’s companies.